As a project that combines “phenomenology and autoethnography with queer theories” (Abstract), Techne: Queer Meditations on Writing the Self interweaves stories on multiple levels and via multiple media channels in order to represent complex human beings in some of the many facets of their lived lives. There are glimpses of everyday stories, as we meet the authors through videos in which they dance, read a book, snap photos of interesting graffiti, compose elegies, or work in the garden. These images and video clips, rendered throughout primarily in black and white, provide visual counterpoints to verbal explication (both written and spoken) that experiments with typeface and vocal alteration.

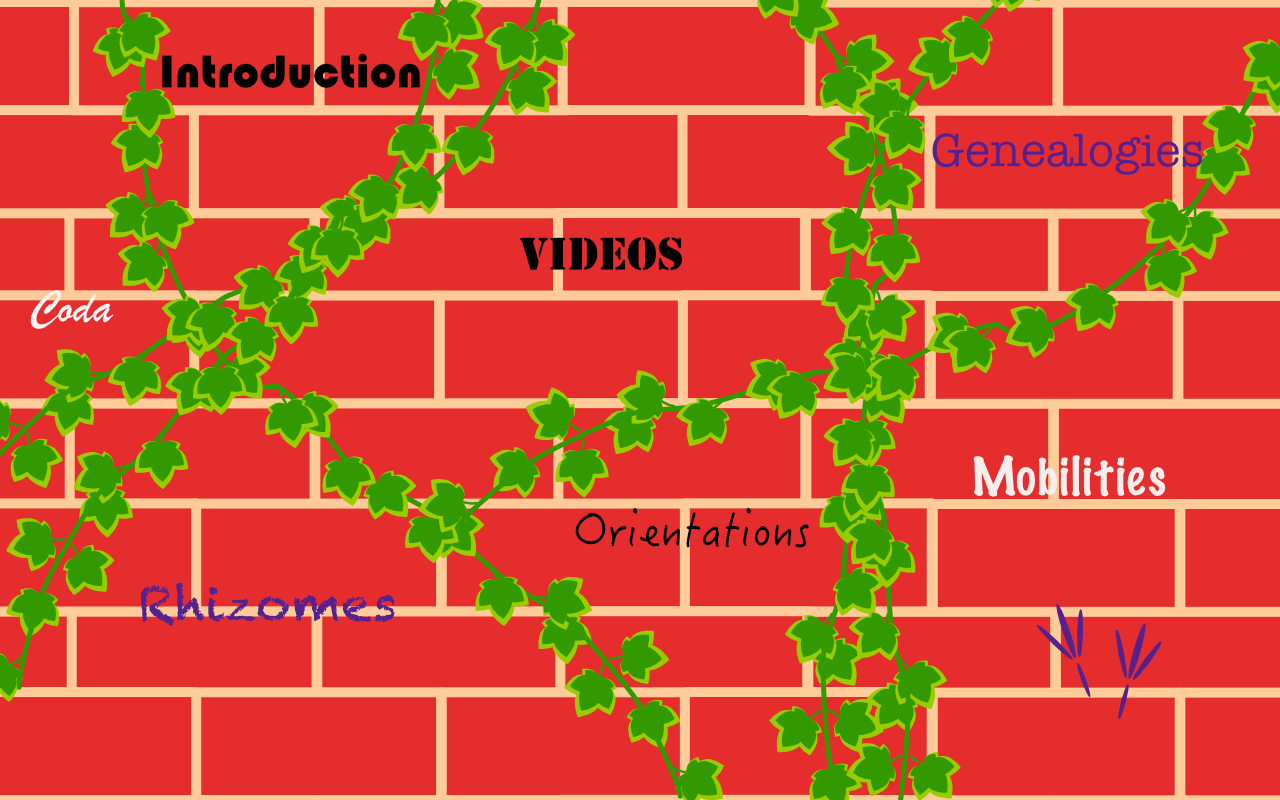

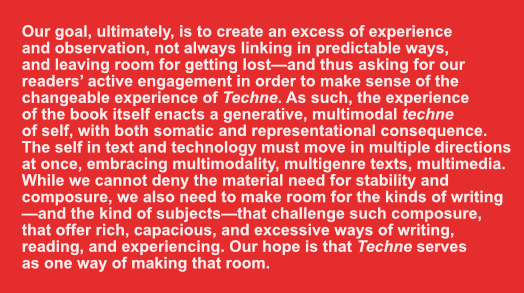

Along with these quotidian snapshots, the authors share deeper explorations of their own stories and experiences of growing up queer: of working through multiple rhizomatic layers within oneself in discovering what it means to be a lesbian in Montana (“Rhizomes”) or writing one’s own genealogy through an act of simultaneous connection and dissociation as family members give a gay nephew the photos of a deceased gay uncle (“Genealogies”). Though at times the multiple layers of image, video, sound, and story fragments can seem overwhelming or confusing, the authors identify “leaving room for getting lost” (“Introduction: A Note on Structure”) as one of the goals of their project. These story forms, as they note, challenge the reader to slow down, to stop and reflect, to counteract the engrained orientation of high-paced media updates and predetermined technological narratives (“Introduction [2b]”). For particularly confusing videos or images, the thorough descriptive transcripts provide an additional layer of insight into the authors’ storytelling goals.

Techne’s stories are deliberately subversive and even playfully so, like graffiti (“Mobilities”)—but it is epistemologically motivated play (“Intro [3b]”) that experiments with performing “embodied narrative as rendered through multimedia to explore possibilities for reorientation” (“Orientations”). In sharing these narratives, the authors invite readers into their exploration of what it means to write the self, particularly in a historical moment that increasingly recognizes the impact of curated data, nonhuman agents, and intricately networked writing environments on human subjectivities. In such a context, the authors argue, it is crucial for writers to be able to recognize the ways in which the tools they use to compose orient them towards particular subject positions (and these positions’ ideological consequences)—and, when desired, to actively resist these imposed orientations in order to pursue more “livable lives” (“Intro [3b]”).

The project is left open-ended with a coda rather than a conclusion; readers are encouraged to join them in continuing the project through participation on a wiki or through submitting their own YouTube videos similar to those crafted by the authors and comprising a significant part of their performed argument. I can’t help but wonder what kind of creative response stories a webtext like Techne might invite—perhaps, in keeping with the authors’ own arguments, responses that both connect to the original project and offer resistance at the same time. With a text that encourages many channels of reading and interaction in both argument and performance, what might a resistant reading of Techne look like, and would there be space for such a reorientation to become part of “Techne 2.0”?