II. Overview

<<

>>

Having traced the methodological foundation upon which I am drawing in order to pursue autoethnographic work in investigating webtext composing and changes in organization across drafts, I now turn to an overview of my work in carrying out an autoethnographic research project. I begin with a brief account of my digital composing background in order to sketch out the context from which these projects emerged. I then describe my data collection activities and trace out my working hypotheses based on the data collected thus far. Finally, I close with an introduction to the three focal projects which will be the subjects of investigation in the following chapters.

A. Background as Composer

Like Whittemore’s memory workers, every composer approaches the webtext design process with a set of skills and interests developed through prior experiences that shape their approach to the project. Give the exact same task or data pieces to Jody Shipka, Paul Muhlhauser, Susan Delagrange, Dan Anderson, or Karl Stolley, and the resulting projects will turn out very differently based on their unique approaches. Shipka, for example, may produce a vintage, tastefully kitschy, somewhat uncanny video to explore embodied literacies in everyday life; Muhlhauser, a funky, quirky visual display that delights in irreverent wordplay; Delagrange, a piece with a polished, early modern aesthetic and exquisite attention to visual ararrangement; Anderson, a video incorporating layered drafts and composing interfaces across time; Stolley, a carefully coded and HTML-validated piece made entirely from open-source technologies. Webtexts highlight these individual approaches in an especially visible way due to the increased range in potential composing channels. Since the design plays such an important role in making an argument’s webtext, exploring a webtext composer’s individual background helps to illuminate how their experiences may influence the argument’s implicit performance via the design.

Here I present an overview of how I came to webtext composing in order to contextualize the design process that my data captured and analyzed in this study. I share these experiences, opportunities, and connections not as a model, but rather to make more transparent how my background impacts the kinds of scholarly knowledge I make and the projects I pursue.

1. Experiences

I came to digital composing, somewhat circuitously, via Wagnerian opera. While working as a dramaturgy intern at Staatsoper Hannover on a production of Siegfried, I became fascinated by Wagner’s concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork that combines multiple sensory channels in order to create an engaging aesthetic experience. Discovering Wagner’s operas had been adapted as a graphic novel by P. Craig Russell sparked my interest in storytelling across media, multimodality, and narrative semiotics. I began to try my hand at digital illustrating work in PowerPoint after seeing the geometric bird artwork of Charley Harper, having a longstanding love for painting and drawing birds. PowerPoint led to Illustrator and Affinity Designer, and I began to pursue both creative and scholarly projects that would give me the chance to develop my abilities as an amateur graphic designer.

2. Connections

Upon my arrival as a graduate student at Ohio State, I learned about webtext scholarship after Cindy Selfe sent out invitations for a review of The New Work of Composing. After clicking through introductory pages of my first webtext encounter, I immediately wanted to learn how to do that kind of work. I was not particularly interested in digital technology for its own sake at the time, but it seemed like an area of study that would allow me to combine my interests in media, storytelling, and semiotics. This initial stumble into digital media, under Cindy Selfe’s guidance, quickly consumed my graduate career and scholarly interests. I took classes and went to workshops; I participated in Ohio State’s Digital Media and Composition (DMAC) Institute, first as a participant, then volunteer, then staff member and finally associate director; I worked in the English department’s digital media center as a tech consultant; I taught classes and workshops. As she has done for so many others, Cindy acted as my digital literacy sponsor (Brandt) and invited me into Ohio State’s robust community of practice around digital composing (Lave and Wenger; Bahl and Clinnin; McGrath and Guglielmo).

3. Opportunities

During my first summer in graduate school, I took an independent study with Louie Ulman on HTML and CSS coding. He introduced me to a free and open source platform (Aptana Studio) for learning web editing. Because I was unable to afford software such as Dreamweaver at the time, Aptana Studio was an important tool in providing me space to explore as a web editor that I might otherwise not have been able to access. I then began to work on developing a creative webtext project with a friend in folklore, an area in which I was pursuing an interdisciplinary specialization parallel to my digital media work). I also worked as an editor at the online journal Harlot of the Arts, which gave me the chance to act as web designer for a first scholarly project; upon Harlot’s break I began as design editor for Computers and Composition Online and assistant editor for Kairos, where I’m currently working. These experiences gave me opportunities both to create webtexts and to learn more about the infrastructures (Ball and Eyman, DeVoss et al.) behind webtext publishing.

With the help of these experiences, connections, and opportunities, at the time of writing I’ve been involved in two published webtexts, two accepted for publication, two submitted for review, and two in progress (along with several failed or incomplete projects that never made it beyond the brainstorming or drafting stages):

Published

Submitted

In Progress

In looking back at this list of past and current webtext projects, I am struck by the fact that all my webtext collaborators have been women, but they come from a range of academic ranks, ethnicities, spiritualities, disciplines, and sexual orientations. I am deeply grateful to them for the opportunity to collaborate, and for all that I have learned from them through our work together. I also gratefully acknowledge the impact of countless other mentors, male and female, including Cindy Selfe, Scott DeWitt, Louie Ulman, Ben McCorkle, Michael Harker, Kate Comer, Kris Blair, Kaitlin Dyer, Paul Muhlhauser, and all those without whose guidance, influence, and critique I would not be able to pursue webtext projects. Though this is an autoethnographic study and the lens is on three of my projects (and literally on me, through the video recordings), this work would not be possible without my collaborators, and those with whom I’m in conversation. I hope these examples of networked composing, and the many, many collaborators to whom I’m indebted, can serve as a way to foreground the possibilities of webtext composing to enact feminist rhetorical principles of collaboration, situated knowledge, and embodiment (Royster and Kirsch) in the presentation of research.

B. Data Collection

Beginning 1 May 2016 and as of 24 February 2017, I have collected data from 142 days of composing sessions on three webtext projects: a book chapter, an article, and a review essay. These composing sessions range in length from 15-20 minutes to 15-20 hours, with varying degrees of breaks. Brainstorming, ideas, and influences on the projects between composing sessions were recorded as peripheral data in a separate handwritten account. Activities pursued during these composing sessions include reading, notetaking, source gathering, creating mockups, illustrating, coding, audio composing, video composing, seeking models or inspiration, drafting, revising, polishing, and engaging in conversations in person or via email with various collaborators. These activities are contextualized amidst practices of taking breaks, managing stress, troubleshooting, scheduling, and cognitive attunement (Prior and Shipka).

For each session, I began by writing down my goals for the composing session, along with any additional relevant contextual notes to document the material circumstances in which I was composing (location of composing, food or drinks, clothing, events or circumstances, deadlines, and so forth), as well as the time and date. I continued this written log throughout the composing session, noting pauses, reasons for leaving the space, and other material influences along with the time. After setting up my initial written notes, I started a video recording from a Zoom cam plugged into my laptop (the only computer I used during data collection sessions) and also started a screen recording. All recordings were labeled by date and saved to a 3TB external hard drive with a folder labeled by date. Also saved in that folder were all drafts completed that day (copied from the previous composing session’s folder and edited in the current day’s folder) and any additional relevant materials such as new secondary sources and media files. After ending the session, I typed up my handwritten notes and added a reflection on my foremost thoughts at the end of the session, such as affect responses, evaluation of how I thought the session went and what I was able to get done, and plans for what I wanted to accomplish next time.

As I grew more comfortable working with the autoethnographic recordings, I also began to add a “working notes” section to my overall notes, to capture my in-the-moment reflections as they unfolded in time with the screen recording. I don’t tend to verbalize aloud when I write, so these “write-aloud” notes were easier to sustain than “think-aloud,” verbalized protocols that would have been distracting for my own working style. I recognize, though, that spoken data can be a valuable information source, especially if that’s already a part of a composer’s working practice. I would suggest that researchers interested in conducting long-term autoethnographic studies consider what kinds of data collection practices they can sustain without too much distraction to their typical composing practices.

C. Limitations of Data Collection Approach

A disadvantage to my recording procedures is that I recorded the video and screen recordings via separate devices/programs (laptop vs. Zoom recording); in terms of lining up the two recordings, I can usually get them very close (within a second or two), though I can’t guarantee that they’re precisely synchronized. I also did not capture video of every single composing session; some (such as those on the bus, or key moments of conversation with collaborators) were recorded via notes or screen recordings, or written notes immediately after the conversation, but due to the transitory or public nature of recording (or the private nature of the conversation), video recording was inappropriate at the time. Since the video recording is stationary, I also do not have documentation on activities outside the composing space during the session (which I tried to make up for by handwritten time-stamped notes on my reason for leaving the space).

Additionally, I did not begin adding my “working notes” section until later in the process, which makes that data contextually strong but more challenging to use for longitudinal comparisons (and also means that potentially key data was lost because it had not been taken into my methodological considerations from the beginning). Furthermore I had a disadvantage looking back at my composing data from an autoethnographic standpoint in that I may not question some of the implications of my design choices (technology, practices, organizing principles) because they seem commonsense or overly natural to me; I attempted to counteract my bias towards naturalizing my own practices through checks and balances in comparison with other composers’ accounts of their webtext design practices.

D. Data Categories

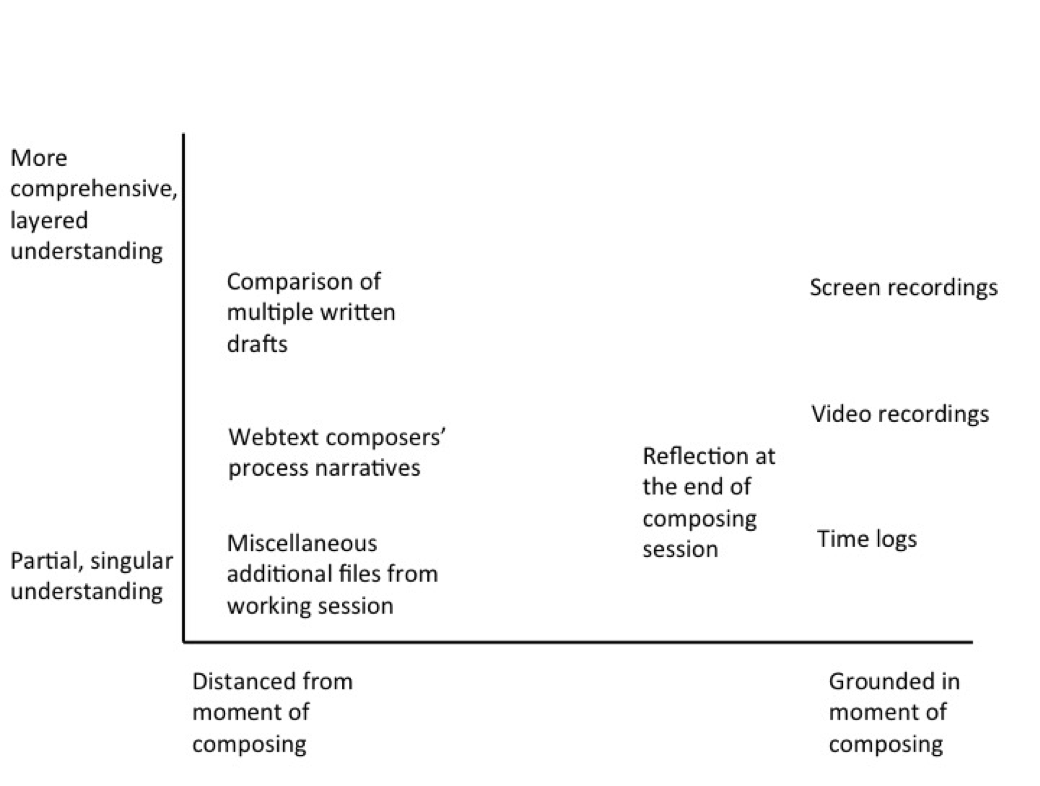

Overall, my recorded data represents a range of recordings capturing information in close proximity to the act of composing, which helps to add to a more complete (though always partial) account of the work enacted. Based on Takayoshi’s (p. 6) characterization of composing process recordings, the data I have collected can be characterized according to the following chart:

Figure 1: Composing data dimensionalized by proximity to moment of composing and depth of insight afforded into composing process.

This chart breaks down composing process data along two dimensions: proximity to moment of composing and partiality of understanding. For example, both my screen recordings and time logs were grounded in the moment of composing, but the screen recordings give a much more comprehensive picture of the composing process than a jotted note on my reason for leaving the composing space. Likewise, both comparisons across multiple written drafts and self-reports of the composing process are distanced from the moment of composing, but the multiple drafts give a more comprehensive view of the overall composing process than the single channel of one individual’s recollections and interpretations at one point in time. In between these poles are my reflective responses as a composer thinking back on the process of webtext composing. The post-session reflections occur immediately after the moment of composing, though they only provide a partial understanding of the process because they reflect my immediate impressions at a single moment in time. The miscellaneous files each provide a glimpse into the literate materials involved in a composing session but must be considered amidst the rest of the collected data to contextualize any insights they may offer.

Overall, the collected data generated in the moment of composing for one individual participant enabled me to make detailed claims about one individual’s webtext composing process, with a value placed on depth rather than breadth. With these data, I can look back across several months’ worth of multiply layered composing sessions and observe my precise sequences of composing action on screen, as well as my corresponding off-screen, embodied actions and contexts. I can compare drafts across each session, note key moments of change in a draft’s inscape, pinpoint the forces behind these changes, and evaluate how they affected the webtext’s performance of design-as-argument. I can also see more critically the obstacles that I faced, how these obstacles arose (and why they were perceived as such), and what strategies I used to negotiate with them. These actions may have seemed intuitive and common-sense at the time, but upon closer inspection revealed the cultural and personal assumptions embedded in my own process as a designer and communicator of scholarly knowledge. While this data is personally oriented, it will assist me in tracing the broader contextual threads behind these projects’ developing organizations in a way that memory alone might gloss over or not accurately interpret.

E. Working Model

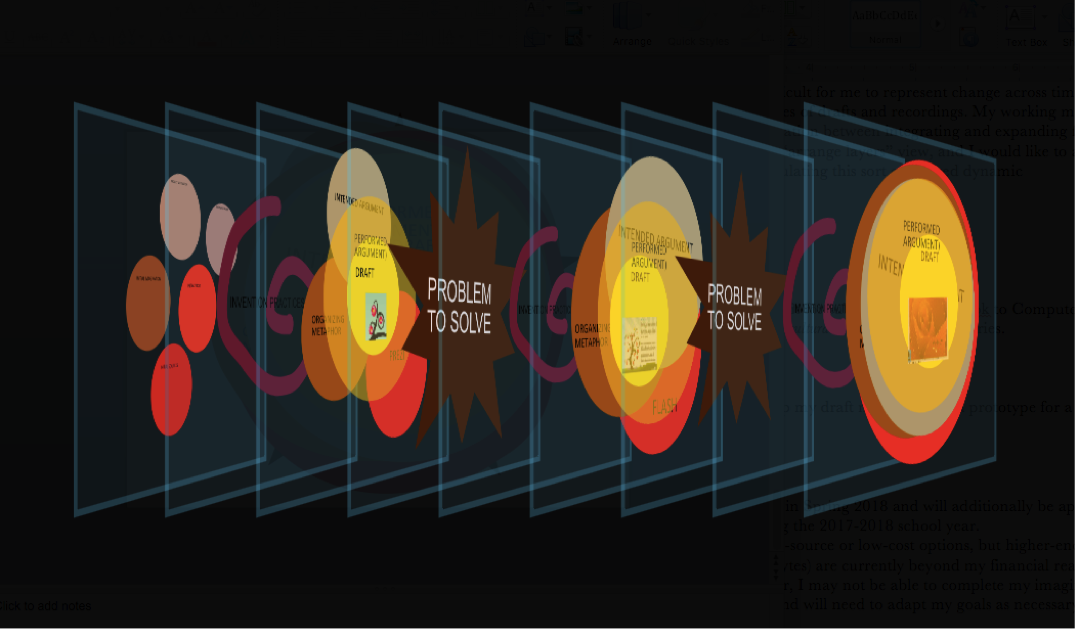

Based on the data collected so far, I have come to view webtext composing as an ongoing attempt to integrate diverse pieces into a cohesive design while negotiating forces and pressures that work to counteract or “explode” that design’s integrated organization. As a composer, I start with a general idea of how I would like to organize a project and the main points I want to explore or claim. I gather a diverse range of media and secondary sources related to these points, then work to bring them together around a central organizing principle (implicit or explicit). Along the way, this organizing principle becomes revised or tweaked as the argument develops, as technical difficulties or new sources are encountered, as the partiality of an organizing metaphor becomes more or less fitting, as colleagues and collaborators suggest new ideas, and as editors or infrastructural pressures raise new options and challenges. Figure 2 illustrates my initial conception of this overall process:

Figure 2: Working model of webtext composing process as ongoing negotiation between integrating and dissociating factors. I created this model as an example using in-process draft images borrowed from Lauer’s published webtext invention narrative in “What’s in a Name?: The Anatomy of Defining New/Multi/Modal/Digital/Media Texts”; Lauer’s project will be analyzed in greater detail along with the case studies in the following chapters.

As the diagram indicates, each round of integrating action by the composer (the purple spirals) brings the component pieces (the multicolored circles) into a more tightly organized assemblage, while new problems that threaten the design’s cohesion (the brown jagged starbursts) appear at intervals throughout the process. There are still some gaps between the components in the final draft, indicating that they never ultimately line up perfectly, but (ideally) they have expanded in scope and are much more fully synthesized than in earlier stages.

With this model as a starting point, I hope to use the detailed webtext composing data and drafts collected over the past few months from the three focal webtext projects (as well as anecdotal evidence from experiences with other webtext projects) to demonstrate that webtext composing is a process of assembling components of various kinds and types into a unified argument. I assume that a webtext composer’s actions are always oriented toward integrating these pieces in some way (rather than deliberately counteracting or sabotaging their own project). I hope to identify which forces serve as “integrating” and which as “exploding” (and to what extent and under what conditions) in the process of creating a webtext’s argument-performing inscape.

I recognize that this model of webtext composing will not correlate to the same experiences of all webtext composers, a fact for which I will account through interviews and examining other authors’ composing narratives to understand the model more fully that they are using, and the degree to which this internal model and their experiences correspond with or differ from my own. However, initial investigations into published webtext invention narratives in Kairos’s Inventio section suggest that other webtext composers experience a similar pattern of synthesizing attempts punctuated by obstacles. A similar iterative dialectic is described in Delagrange’s account of creating her “Wunderkammer” piece, though she describes it as “oscillation”: “Designing scholarship in new media requires continuous oscillation among the text, the images, and the visual and conceptual framework” (Delagrange 2009b, “Design”). As Delagrange notes, this process of “oscillation” (or in my model, “integration”) suggests building a webtext somewhat intuitively out of possibilities raised by each piece a moment at a time, which can be richly productive but also detrimental to the overall cohesion of the project if individual details are developed without attending to the structure and organization of the whole (a case in which the act of “integrating” carries its own “exploding” potentials). Lauer described more of an experience of a long journey being tossed about by forces beyond her control, which had a significant impact on her webtext’s final form. She notes how she felt subject to the “whim of the technology gods” and had to negotiate with limitations that pushed the project’s ultimate fate beyond her control (“A technological journey”). Both descriptions of the webtext composing process imply a negotiation with forces beyond the single composers’ control that must be dealt on a case by case basis, and that have a significant impact on the project’s overall organization--and thus, on the argument which it implicitly performs via its design as a knowledge-making artifact.

Furthermore, I hope that this model of negotiating between integrating and exploding forces in creating a webtext’s inscape will be a useful approach not only for webtext composers, but for all creators of scholarship across media--from essays to PowerPoints to blogs to webtexts, and all the myriad ways in which scholarly knowledge is remediated, translated, reorganized, and transformed in current academic professional communication practices.

<<

>>